His fingerprints can be found on the Red Sox success this season, and hopefully his work will continue.

It’s tough when your obituary has to note who you were not. I saw that more than a few remembrances of Billy Bean noted right away that he wasn’t the Moneyball Billy Beane, and he was the second retired MLB player (naming Glenn Burke as the first) to publicly come out as gay. Having two other people named right away in your own obituary is odd, right?

Billy Bean was used to it in some ways, living life under the radar, in the shadows, being overlooked. But then also he wasn’t: he was prominently in the spotlight for a long time. He was an All-American outfielder twice, and led Loyola Marymount to the College World Series in 1986. He was a highly touted prospect who only spent about a year—total—in the minors.

I was at the Mariners game on Tuesday night when they announced his death before the game and paused for a moment of remembrance. They were playing the Tigers, Bean’s first team. With all our recent trade-deadline talk about prospects, here’s one to note: Bean was one of those coveted prospects who couldn’t make it in the big leagues. His résumé and early successes promised great things, and he started to deliver right away. In his first game, he rapped out four hits, tying a record for a player in his first MLB debut. Detroit fell in love with him. But from those attention-getting beginnings, he made only 519 plate appearances in 272 total games, and retired at 31 years old.

Change up the details a bit and you can find similar stories all over baseball, but one possible reason for Bean’s faded star looms large over his story. Billy Bean was carrying a secret that consumed his life, one that would also change the direction of his future.

He was gay, and afraid to come out publicly. He dealt with this by living a double life. Although he was in a serious relationship with a man and they lived together, he never introduced him to his friends or teammates. In fact, Sam had to hide if someone came over, and he had to find somewhere else to live when Bean was on the road with the team. These were the extreme measures they took in order to stay out of the spotlight. Sam had a medical emergency one night and Billy drove him to a more distant hospital, despite the urgency. Why? So that he wouldn’t be recognized at the hospital where he made public appearances as a player. When his partner then died, he avoided the funeral so that he could keep his secret.

All of this was a terrible weight, to say the least. He wrote a book about being a closeted professional athlete and the lengths he went to in order to stay in the closet.

I read that book when I was in grad school. I devoured it and others because I was then beginning the process of coming out as LGBTQ. Plot twist! I hadn’t even known this about myself, and to finally realize, later in life, something so profound, something so integral…well, there’s no shock like learning that you don’t even know yourself.

There is for sure a streak of homophobia in our culture. It was obvious in the region where I grew up, and it is present in my own family. That made it far easier for me to not look at this part of myself than to buck nearly everything my small-town New England, Irish-Catholic family expected of me. I’m sure that was the reason for keeping this “secret” although it was one I didn’t even know I had.

When the laws changed a few years later, I married a woman, and although we are now divorced, the date of our wedding day just passed. I don’t honor it or anything, but it’s notable as the day my four siblings and I stopped speaking to each other. Not all of them were even there that day, but it was a breaking point. (Since this is journalism, I will fact-check myself and note that after about seven years, one brother and I met for coffee and have since exchanged a couple of brief birthday emails.)

I sometimes wonder, as I guess I’ve come to a more contemplative place in mid-life, what I might have done if I hadn’t had to devote so much time and energy to navigating this part of my life. The shocking discovery, the uneasy living with it, the anxiety over telling my family, the confusion and pain of having them treat me and my then-fiancée so badly, and the ache of essentially having lost them over this…it has all taken so much time and energy. I know that I have it easy in other ways: I wasn’t kicked out of my house as a teen like many queer kids are, the rest of my family (aunts, uncles, cousins) never stopped supporting me for even one second, and I can pass as straight if I need to, for safety. (Safety sometimes includes psychological safety).

So it hasn’t been a bad life despite the bit of turmoil that being LGBTQ has brought with it, and I bet Billy Bean told himself things like that too.

I relate to him because of what we have in common, even if that sounds laughable on the surface. My stakes were high because being true to this part of myself took my immediate family as collateral damage, and that’s a shame. A person could use the support and love of their family. But that’s the way it went with them.

Take those regular-ol’ kinds of high stakes, the sort that anyone might navigate, and then magnify it for Billy Bean. He was in the public eye. A baseball locker room is a close environment, one where misunderstandings and dislike can fester, where team chemistry can be made or lost. Much of this story was playing out at the height of the AIDS pandemic, so mix in the burdens that gay men shouldered because of that; I was only a kid then, but I clearly remember the initial fears and anxiety of not even knowing how it could be transmitted. If we squint, we can probably remember that from the crazy, early days of our most recent pandemic. Add in the fear that he’d go from being a golden boy to being hated by all of America. Or that he’d lose his job.

A psychologist might say that he did exactly that, and that he did it to himself—turned his fears inward and essentially deleted his own career before it ever got going. That he never gave America a chance to know him because he hid. I’m not saying it was conscious, but I’ve been there and I get it. It’s so much easier to fly under the radar, to put off telling your parents you’re gay. Isn’t that funny? I told my parents and one of my closest friends last…because I wasn’t sure if they’d still want me in their lives once they knew, and not telling them let me hang around a while longer.

Billy Bean’s story is his own, not mine, but it’s a little bit about all of us who have held onto this secret, perhaps longer than we should have.

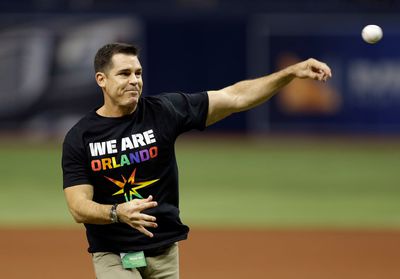

He was very open about all of this in his book. He retired because of the conflict between his sexuality and his love of baseball. He didn’t see how the two could ever be integrated. He moved across the country and started a new life in Florida, going on to have a successful second career in restaurants. He came out as gay a few years after his playing career ended, and I remember how it made national news (as still happens now, but it was even rarer then, and with less precedent, so he got the full blaze of the spotlight).

Except for these public-facing forays, which looked at his baseball past, there seemed to be no baseball present or future for him, until he was on a panel with Matthew Shepard’s mom. Matthew was an LGBTQ advocate simply by living his life openly, while his mother continued this legacy by working to pass hate crime legislation. Their meeting inspired Bean to start thinking about his authentic self. And his authentic self wanted to make things right on some level, and try to make things better for future pro ballplayers.

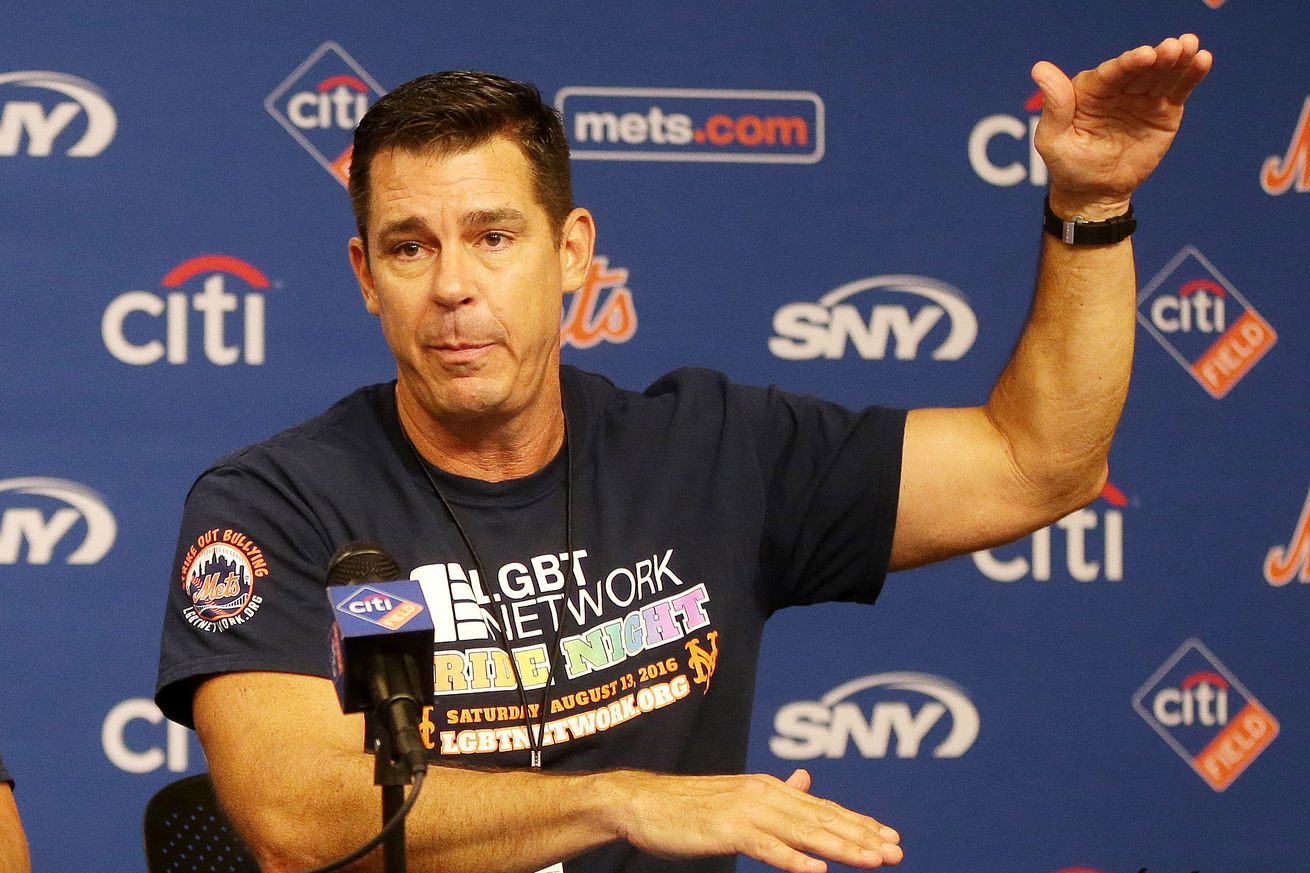

He was hired by Bud Selig in 2014 in a new position that played to this desire, and his MLB experience. He was promoted to his eventual position of MLB’s Senior Vice President of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (also a newly created position). His work focused mainly on workplace culture: educating minor leaguers, preventing bullying, speaking to each team’s clubhouse during spring training, and public speaking.

It occurs to me—and this is pure speculation—could the recent NSFW comments that Cal Quantrill directed toward Reese McGuire be a by-product of this kind of education? In past years, it might’ve been a quick homophobic slur but we ended up with something else. Low-hanging fruit, or some type of progress? We’ll never know!

Bean’s efforts weren’t confined to LGBTQ issues; his goal was to make everyone feel included. One way that his work has affected Red Sox players and fans is in the more honest and transparent discussions around mental health. There’s been an outpouring of support for Jarren Duran and Chris Martin as they’ve shared some of their struggles or utilized MLB’s leave policies to allow them seek help. There’s a general openness in being able to discuss the pressures and fears they’re living with, some of them very specific to the game we love.

Bean said that he was hopeful that MLB would eventually hire more LGBTQ employees. I think baseball has a long way to go with female hires and people of color as well; it doesn’t have a great track record of employee retention in these areas. Some notable failings are undercutting Kim Ng (a team issue, but a cultural one within baseball too), and the decreasing numbers of Black players and managers, which has been happening under our noses for years now. Much of this was out of Bean’s official purview, and the reasons for these gaps are many. I would love to see more Black players in baseball. I would love to see any LGBTQ+ players feel able to come out. As purveyors and consumers of statistics, we baseball fans know that they are already playing the sport we love, probably at the highest level.

And then we learn about players like Matt Dermody, formerly of the Sox. I guess Bean’s training didn’t take in his case. Although Bean’s focus was working with MLB employees, I’d like to see more public results, or to know more about MLB’s efforts behind the scenes. I want its work to be more public so that I don’t have to justify my fandom—to myself, and to others.

Fans of other sports (as well as those who aren’t involved in this silly business of supporting a team with your whole heart) don’t always understand why I love baseball. Arguments typically run along the line of: what can a smart, queer, politically progressive woman who is still in the prime of her life find to love about an old, boring sport that’s trapped in the twentieth century?

It’s a tough one to answer sometimes! Not after an exquisite catch, or a sweet swing, or an exciting win. Those moments are outstanding, but I want to be proud all the time, and to feel like I belong as a queer female fan. MLB sometimes makes that really difficult. The NBA, NFL, and women’s pro soccer are (mostly) proud of their player-activists and progressive role models. In the NBA, it’s been de rigeur for years, thanks to folks like the Celtics’ own Bill Russell. The WNBA wears its heart on its sleeve and publicizes its initiatives to be inclusive—and those initatives include both players and fans. Baseball has had just a few people on the public stage, like Billy Bean, Jack Flaherty, Sean Doolittle, our own Liam Hendricks, and a few others.

Another ally is Brian Cashman, who has publicly grieved Bean and vocally supported his inclusion work. I know this is true because I ran into Cashman and other high-ranking members of the Yankees front office at a gay bar in New York once. They had just presented scholarships outside, in front of a banner and the cameras, but then came inside privately and had some drinks. No cameras. They didn’t have to do that, and they didn’t have to stay as long as they did. Hell, I left before they did! That is meaningful support, if not well known.

I’m sad that it took Bean’s death to have support for his work come forward in a larger way, and that includes Rob Manfred praising Bean’s efforts so forthrightly and enthusiastically. Manfred has his flaws for sure, but I was happy to see that he gave a warm and beautiful tribute, not just to Bean as a person, but to his whole enterprise, his whole second act in baseball.

He made Baseball a better institution, both on and off the field, by the power of his example, his empathy, his communication skills, his deep relationships inside and outside our sport, and his commitment to doing the right thing. — Rob Manfred

I hope Manfred and others persist in their support of Bean’s work, continuing and expanding his initiatives. Baseball will be more vital and can enter the twenty-first century chat if they do.

Bean’s legacy was to try to open doors for others that seemed to be shut for him. Like most pioneers, his works feels incomplete. But I hope that’s because this work of opening doors, creating understanding, and including everyone is really just beginning for baseball.