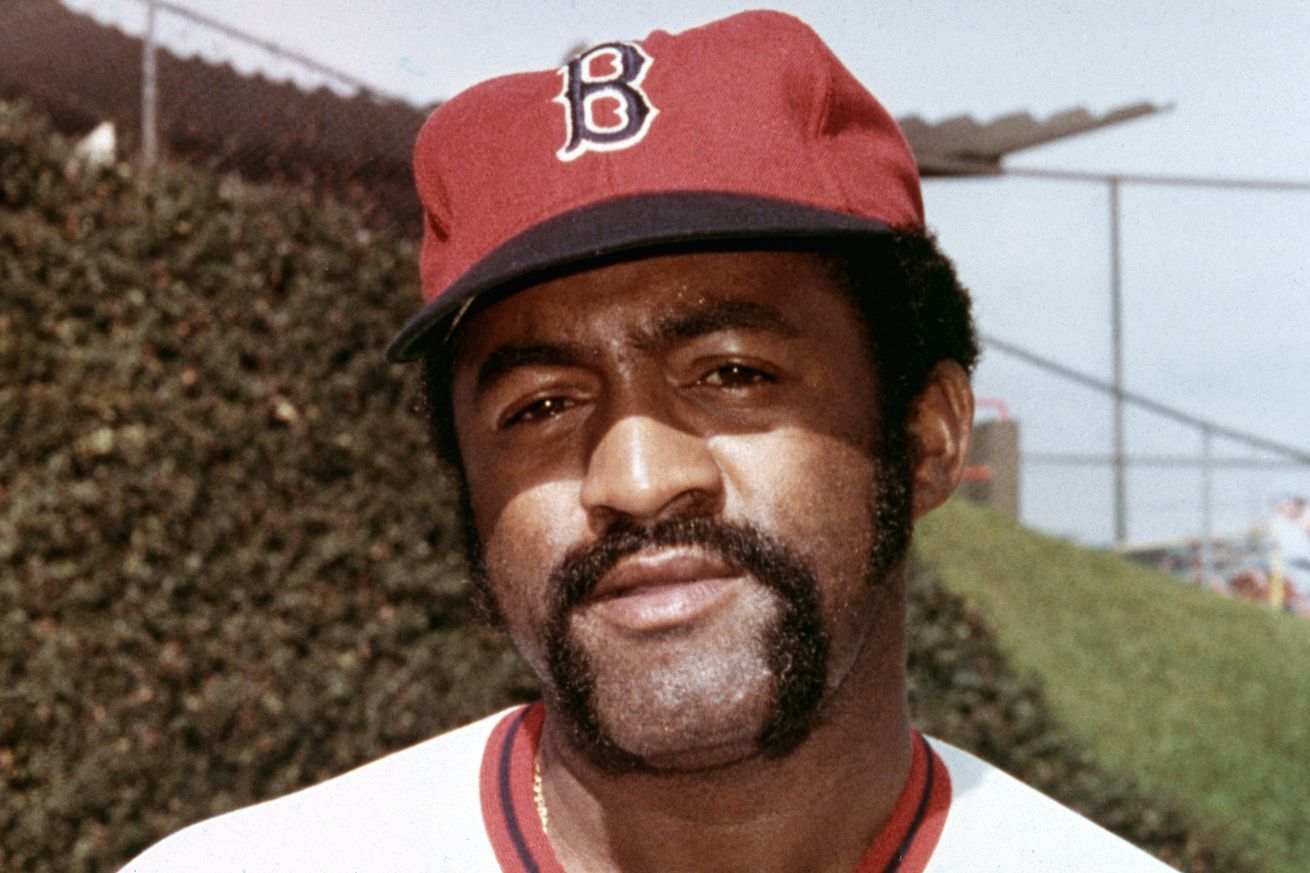

El Tiante was my El Gigante.

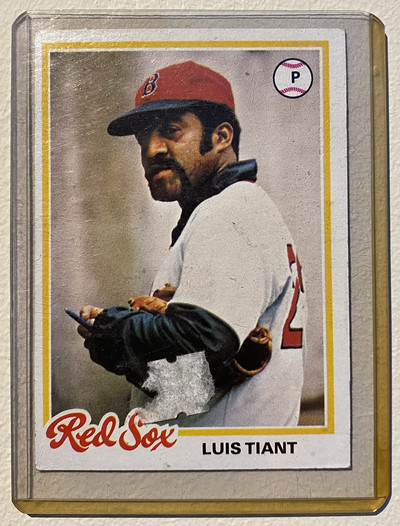

I am not a baseball card collector by any means, but I have acquired a couple of cards here and there. I only look at three of them with any regularity. My best-looking Jim Rice card has been a fixture in my office for years. I recently added two to my bookshelf; they were gifts and I look at them every day. One is Carlton Fisk waving his ball fair. The other is Luis Tiant.

Tiant’s card is from 1978. The back notes that he lived in Milton (such a quaint stat for a baseball card, right?). This tracks because he said many times that Boston was his second home, after Cuba.

He left Cuba to play professional ball but was caught in a truly difficult political situation. Fidel Castro came to power in Cuba in 1959, after a revolution. He soon banned professional sports as well as all travel to and from the island. Although Tiant was given the choice to come home, he stayed with his team in Mexico. It was a one-time offer; in making his choice, he was consciously, if sadly, closing the door to ever returning to a life in Cuba. His father, who understood that there were no legitimate baseball opportunities for him in his home country, supported Luis in his decision. The Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and the resulting embargo on trade and travel with the US (which continues) compounded this situation.

So Luis chose baseball instead of home and family. His career flourished because of it. From Mexico, he went on to Cleveland, where he made a big splash. His ERA in 1968 was 1.60, and that ERA still stands as the lowest for an American League pitcher in the post-integration era. He became an All-Star for the first time. He racked up accolades and accomplishments. He could seemingly do anything and go anywhere—almost. He still couldn’t go home.

Luis was moved to tears, and often, by seeing his Cleveland teammates having fun while he worried about whether his family had food to eat. (Without saying whether or not I’ve been to Cuba, I will say that he was right to worry. The deprivation is real.) In subsequent years, he spoke with genuine sadness about what it meant to not be able to go home.

Peter Gammons has called him the best player who’s not in the Hall of Fame. Others have noted the best moments of his nineteen-year career so I won’t do that. Many happened before I was born, or when I was too little to understand, but I understood at some point that he was great.

I actually believed for many years that his nickname was El Gigante, instead of El Tiante, and I was shocked many years later to find out I was wrong because it had felt so right. I suppose that was little-kid ears, mishearing or misunderstanding something, but I knew it meant Giant—I’m sure that was due to Sesame Street—and that made all the sense in the world to me. That was the kind of buzz he had around him for sure, and I knew about it because he came to Boston. That was an indirect result of breaking his shoulder blade while throwing a breaking ball (the irony!).

The injury eventually forced him to adapt his delivery, in order to make up for his decreased velocity. That crazy-beautiful delivery. I do remember that. Standing straight and still while his glove ticked down toward his waist in perfectly timed increments—it used to make me think of the sand draining down from a board-game timer. And the kick. The looking around, at all angles. It was so weird, and so beautiful in its weirdness. Was it fast or slow? I’m still not sure! It was a little bit of everything.

He revitalized his career with that delivery during his time with the Red Sox. Also during this time, Tiant’s parents received permission from Castro to travel to Boston and watch him pitch. It had been seventeen years. They arrived in the summer, not long before the 1975 World Series. I said I wasn’t going to get into listing his accomplishments, but I lied a little. In the 1975 World Series, he started three games—and two of them were complete games! All Red Sox victories came in games that Tiant started! That crazy, historic, and ultimately heartbreaking Series.

When I played baseball with my brother in the front yard, the little bump of a hill that an oak tree dominated was our pitcher’s mound. The way we laid out our imaginary field, home plate was where the driveway met the grass, opposite the oak tree. First base was a bush with a lamp in the middle of it, and on it went around the yard, with various natural features carving out our field. In this configuration, the pitcher had to stand just in front of the giant oak in order to face the batter. I remember that my delivery involved turning around and staring right at the scratchy bark before spinning and releasing the ball. That was pure Luis.

In remembering Luis this week, I saw a clip of Peter Gammons saying that anytime Luis pitched would be a good time to initiate a crime spree in the Boston suburbs (presumably because everyone was riveted to the TV, or at the game themselves). That feels right. That’s the Red Sox I grew up with. Luis was a huge part of those teams, and the legend, and the feel of that time. Even a little kid knew that.

Thank you, Luis Tiant, mi gigante, and goodbye.